"While hunting the pilot whale has helped the Faroese survive a harsh environment over countless generations, the very same poisons that threaten the whales now threaten the people eating them.

But there is no need to end the Faroese' special relationship with the pilot whale, but simply redefine it: For these incredible animals can still provide for the Faroese through whale-watching, rather than as food, in a way that will help sustain both whales and the Faroese far into the future."

- Sir David Attenborough: Broadcaster, London

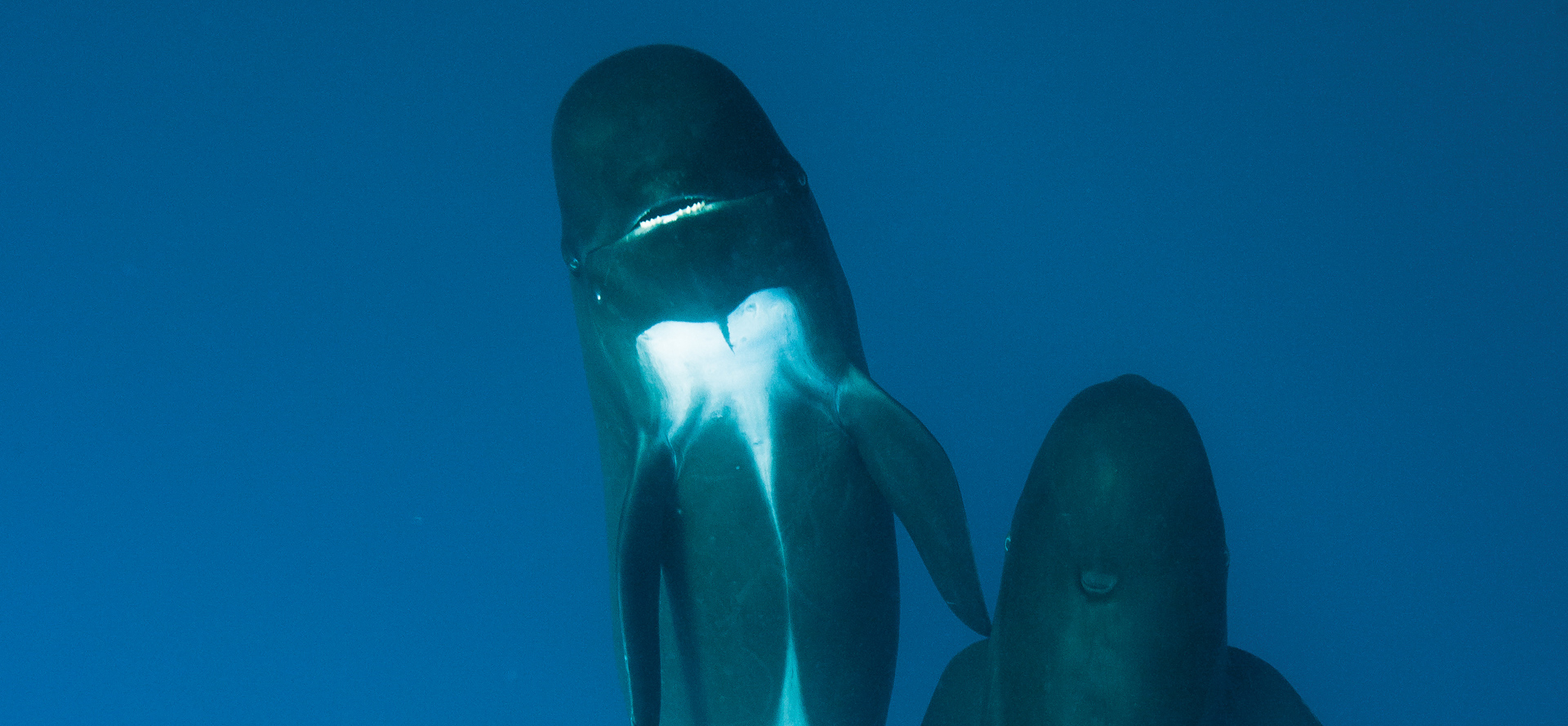

The long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) or grindahvalur is one of the largest members of the dolphin family. It is a living symbol of the Faroe islands, one that has sustained the Faroese for many centuries, yet has frequented these waters for many millions of years.

Pilot whales live in family groups or pods which consist of females and their young, along with older animals. A typical pod will be almost 70% female and to avoid inbreeding they will only mate with males from other pods. Such female-led lifelong family groups are rarely seen in the animal kingdom and a characteristic pilot whales share with elephants, ourselves and other primates.

Most mating occurs in summer, with calves born 12 months later. A calf will suckle for three years or more. All pod members play an important role in looking after the young. Older females will care for and even nurse calves at the surface while their mothers are away feeding.

A female will produce only one calf every four to five years, and just three or four calves in her lifetime. This low reproductive rate makes these animals particularly vulnerable to environmental changes and other threats.

A female can live for 60 years or more with males around 45. Mature pilot whales can reach over six metres in length and weigh over two tons.

They are also highly social animals, using a sophisticated repertoire of clicks and whistles to communicate with one another. They also use sound to navigate and hunt for prey in the ocean depths.

Pilot whales live in family groups throughout their lifetimes. Mothers have been documented carrying dead calves for days, strong evidence of their strong social bonds and their capacity to mourn for a lost family member. Juveniles cannot dive to great depths and they remain at the surface attended by older animals while the rest of the pod dives for food.

Research suggests that different pods have their own unique vocal repertoires called dialects. Scientists believe that they use these sounds to exchange information and to identify each other, reinforcing social bonds. It's a kind of language, if you like. Scientific research also suggests that unique calls are passed from one generation to the next as a cultural legacy, a characteristic these whales share with sperm whales and orcas, as well as ourselves and some other primates.

Sometimes large groups of pilot whales will come ashore together and eventually die, often trapped by an outgoing tide. These events are little understood and people will make great efforts to save them.

Perhaps the whales' sonar has been confused by weather conditions, underwater topography, or even seismic activity. Loud noises generated by human activities such as seismic testing for oil and gas, or the use of powerful military sonar may have frightened the whales or even caused internal injuries. The whales may become trapped supporting a sick pod-member, at risk of drowning, as they accompany them into the shallows.

Many populations of whale and dolphins have fallen by up to 95% or more. Sadly, several species and populations are now critically endangered, while others are under increasing threat from environmental changes caused by human activities.

It is very difficult to accurately count whales. Sightings surveys can be used to estimate a population size, but cannot show if it is stable, increasing or declining. The last survey of the pilot whale population estimated that there could be as many as 700,000 animals in the north-east Atlantic and this is often used to argue that an average annual catch of around 7-800 whales is sustainable. However, this survey was conducted some 20 years ago and increasing threats are taking an unseen and increasing toll.

New whaling regulations have been introduced in order to try and reduce suffering and quicken times to death. These mandate the use of the spinal lance and round-headed gaff as the principal implements in place of the whaling hook and knife. Additionally, anyone wishing to take part in whaling needs a license to do so and will have undertaken a special training course on the new whaling methods.

While any improvements to killing methods and death times is welcome, the driving and killing process will still inflict fear and distress upon the whales who will ultimately be killed in front of one another. Whether the use of the new spinal lance can inflict a near instantaneous death in the often chaotic environment of a large grind is also open to question.

Pilot whales exhibit complex behaviours, a strong sense of society and even a culture. They are very like us in these respects. As large brained, highly-evolved and sentient creatures, there is little doubt that the whale drive and killing process inflicts fear and distress, as well as prolonged physical suffering upon these animals. Additionally, the killing of entire family groups in front of one another, including pregnant and nursing females, raises serious ethical questions, especially when these hunts no longer provide essential, or even safe food.

Heðin Brú, 'Feðgar á ferð' ('The Old Man and His Sons')

There are almost 90 species of whales and dolphins alive in the world today and these are divided into two groups:

The baleen whales, like the enormous blue whale, use bony plates in their mouths called baleen made of keratin, like our fingernails, to sieve plankton and small fish from the water. Humpback whales often make bubble nets to concentrate their prey into huge mouthfulls that they then sieve from the water through their baleen plates.

Some baleen whales are truly huge, growing bigger than the largest dinosaurs. This blue whale is some 30 meters in length and weighs a staggering 150 tons. Even a newborn calf is seven metres long and weighs three tons!

The toothed whales, such as the sperm whale, the orca or killer whale and other dolphins and porpoises are active hunters, using echo-location to catch fast moving prey like fish and squid, or other sea-mammals like seals and even other whales.

The largest toothed whale is the sperm whale, made famous in Herman Melville's epic novel Moby Dick. This 18 metre long, 60 ton giant possesses the largest brain to have ever evolved. There is no doubt that such a large brain - almost six times heavier than the human brain - must have evolved for some purpose.

Whales can be very long lived. While fin and sperm whales can live for over 100 years or more, harpoon tips have been recovered from bowhead whales in the high Arctic that reveal these whales can live for an astonishing 200 years!

Sadly, the commercial hunting of the great whales has devastated one species after another. For example, around 350,000 blue whales were killed in the 20th century alone and just a few thousand blue whales survive today, possibly too few to ever recover.

The relentless pursuit of the great whales for their oil and meat was only abandoned as numbers collapsed and they became uneconomic to hunt. So populations of the blue, fin, right, bowhead, humpback, sei, Bryde's, grey and sperm whales all plummeted by up to 95% or more.

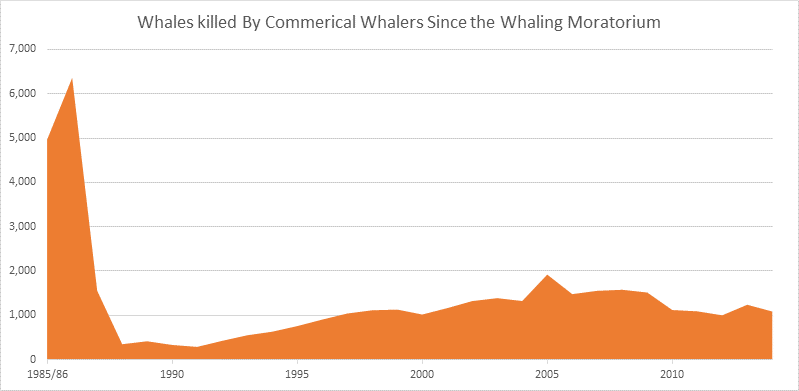

With extinction looming for some species, an indefinite ban on hunting great whales was introduced by the United Nations-backed International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1986. However, almost 40,000 whales have been slaughtered since by a handful of nations that defiantly continue commercial whaling. Today, the smallest species of baleen whale, the minke whale, is hunted for meat even though serious questions remain over the status of the populations being targeted and despite the increasing threats they face.

Small whales and dolphins, including pilot whales, are hunted in very large numbers around the world outside of international regulation and controls.

Climate change is warming ocean currents causing significant shifts in the location and abundance of vital prey species.

Toxic industrial pollutants accumulate and concentrate in dangerous quantities in the organs, meat and blubber of whales and dolphins. This poses a serious threat to these animals and anyone consuming them.

Up to 300,000 whales and dolphins drown in fishing nets every year. Many more die from ingesting marine debris like plastics, which they mistake for food.

Commercial overfishing causes fish stocks to collapse reducing food for whales as well as their prey. Even krill, a staple diet for baleen whales is now being commercially harvested in huge quantities.

Increasing noise from shipping interferes with the whales' communication and unknown numbers are struck and killed by ships they simply cannot hear or avoid.

Powerful military sonar and oil and gas exploration produce noise at huge levels which is harmful to whales and dolphins.

One of the greatest threats to pilot whales comes from toxic pollution. Since 2008, Faroese health leaders have warned that pilot whales are no longer fit for human consumption and should not be eaten. Toxins in the meat and blubber, traditional dietary items for many Faroese, can cause cancers and seriously damage the nervous, immune and reproductive systems.

Contrary to this advice, the Faroese Government has recommended that people can consume no more than 250g of meat in a month, and that children and pregnant women or women wishing to become pregnant should avoid eating it altogether.

Yet despite the health warnings, an average of 7-800 pilot whales and sometimes large numbers of dolphins and several bottlenose whales may be killed each year. This produces quantities of whale products that exceed many times over, even the Faroese Government's recommended 'safe' levels of consumption.

Cancer, Parkinson's disease, arteriosclerosis, reduced fertility in men and women, diabetes, and inhibited fetal development are just some of the serious health concerns linked to ingestion of such toxins.

A new campaign has been launched in the Faroe Islands by Grindahvalur, a British and Faroese organisation created to provide unbiased, up-to-date, scientifically-based information about pilot whales, toxic pollution and public health. A copy of the press statement can be seen here.

On January 1st a billboard advertisement was erected in central Torshavn to highlight the threat posed by industrial poisons, both to the whales and the people that consume whale products. It recommends people eat more fish, and not pilot whale, for a healthy life. The billboard can be seen here.

This has been followed today with a public information brochure that has been delivered to every Faroese household. It provides up-to-date factual information on the dangers posed by toxic pollutants that concentrate up the food-chain into the whales and the people eating whale products. The brochure can be read here.

Dr. Pal Weihe, Chief Physician at the Department of Occupational Medicine and Public health in the Faroes has raised his concerns on this issue many times over the past 30 years. He believes that pilot whale is not safe for public consumption and his views on the dangers posed by these toxic contaminants are supported by international scientific research.

Further information on this subject can be found on this website.

"I currently work as a food safety consultant but I have also worked in the animal welfare industry and over the past few years I have become very worried about the future of whaling here in the Faroes.

While I am naturally concerned with food safety, I am also deeply troubled by the inherent cruelty involved in whaling and the threat it poses to the future for these animals by diminishing the gene pool. I have grown equally interested in the whales, and the more I have learned the more I realise what amazing animals they are and also the scale of threats they now face.

I think it is time to consider a different future, one for the whales and the Faroese."

"In a way, you can say that we have asked the Faroese public to give up a traditional Faroese food, because this food has been contaminated by global pollution. This is not pollution created in these islands; this is pollution coming from international society.

What I'm hoping is that the sacrifice from the Faroese public to give up the traditional food can actually be used as a message to the surrounding world; that we should be more careful with our oceans, because if humans can suffer from these pollutants, it is well imaginable that these sea mammals can suffer as well."

"In 2014 I went pilot whale watching in Tarifa in southern Spain. As a Faroese myself, it was amazing to see these animals alive and swimming free in their natural element. I believe watching whales, and not killing them, is a future that would benefit the Faroe Islands as well as the whales."

"I believe if the whaling stops, it will be good for whale-watching and for the tourism industry on the Faroe Islands. Because I believe the whales will be in the fjords and around the islands."

"The Faroese don't need whale meat anymore, especially not when it's poisoned.

In the old times, we needed it, and without it, maybe we wouldn't be here. But not now, and of course we should stop killing them. Also because our own scientists say they are poisoned; their meat is poisoned, so we need to stop what we are doing."

"The most special thing about pilot whales is that they stay in family groups. This is very rare in the animal kingdom. They are highly social and they stay with their mums, sisters and brothers, in the same group.

On the other side we have many threats that pilot whales and other cetaceans have to face these days and at the same time nobody knows how many pilot whales are out there in the Northeast Atlantic. Looking at all this, it tells us one thing – we just shouldn't kill them."

"While hunting the pilot whale has helped the Faroese survive a harsh environment over countless generations, the very same poisons that threaten the whales now threaten the people eating them.

But there is no need to end the Faroese' special relationship with the pilot whale, but simply redefine it: For these incredible animals can still provide for the Faroese through whale-watching, rather than as food, in a way that will help sustain both whales and the Faroese far into the future."'